Construct an Undo Tree From a Linear Undo History

Table of Contents

Emacs comes with a powerful but arguably strange undo system, it considers the action of undo themselves undo-able, so instead of redo, you just undo a previous undo. This allows you to return to every previous buffer state, something a conventional undo system doesn’t guarantee. But Emacs’s undo history can easily get out of hand when you undo, then undo that undo, then undo the undo of undo… You lose your mental model of the undo history very quickly and end up holding the undo button until you see the desired buffer state.

One idea to take advantage of both worlds is to use an undo tree. An undo tree is easy to navigate and understand. The ubiquitous undo-tree.el is exactly for that. As a coding challenge, I have been thinking about how to construct a tree out of the linear undo record. That way we can avoid keeping an internal data structure of undos like undo-tree does. This post describes the way I figured out to do that.

1 How does undo work in Emacs

;; An example of `buffer-undo-list'. (nil (11369 . 11377) ; Insertion from 11369 to 11377. nil (11332 . 11344) ; Insertion from 11332 to 11344. ("<li" . 11332) ; Deleteion of "<li" to 11322. nil (t 24653 33109 208947 953000))

Emacs keeps undo records in buffer-undo-list.

Every time the buffer content changes, Emacs pushes multiple

entries onto the list, each representing a change like

insertion, deletion, etc. These entries are grouped by the

nil entries as delimiters, so multiple actions

can be undone at once. Here I’ll call a group of entries a

“modification”.

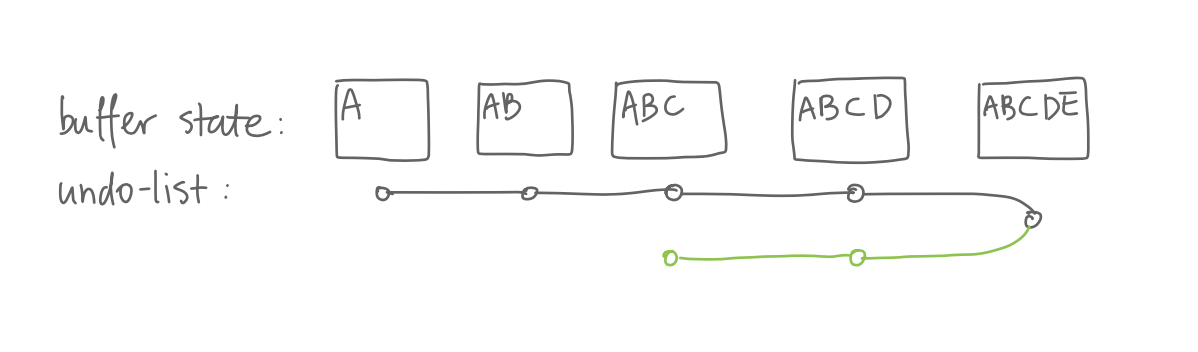

For example, if I insert “ABCDE” into a buffer 1, and undo

twice, I’ll see “ABC” in the buffer, and two undo

modifications would be pushed onto

buffer-undo-list, one for deleting “E” and the

other “D”. If we keep undoing, we will keep going back until

all edits are undone.

To stop undo and start redo, we press C-g

which breaks the undo chain 2. All the undo records we

just created are now considered ordinary modifications and

further undo undoes these previous undo’s. So if we undo

twice, we are back to “ABCDE”.

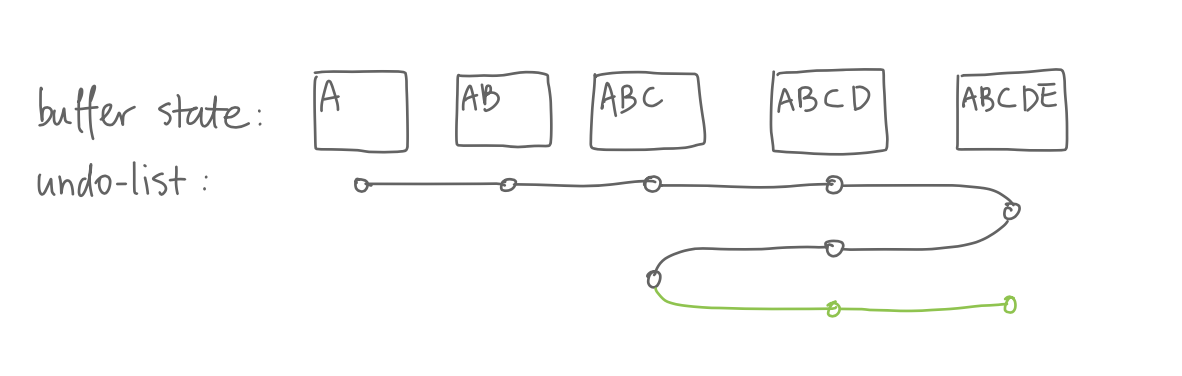

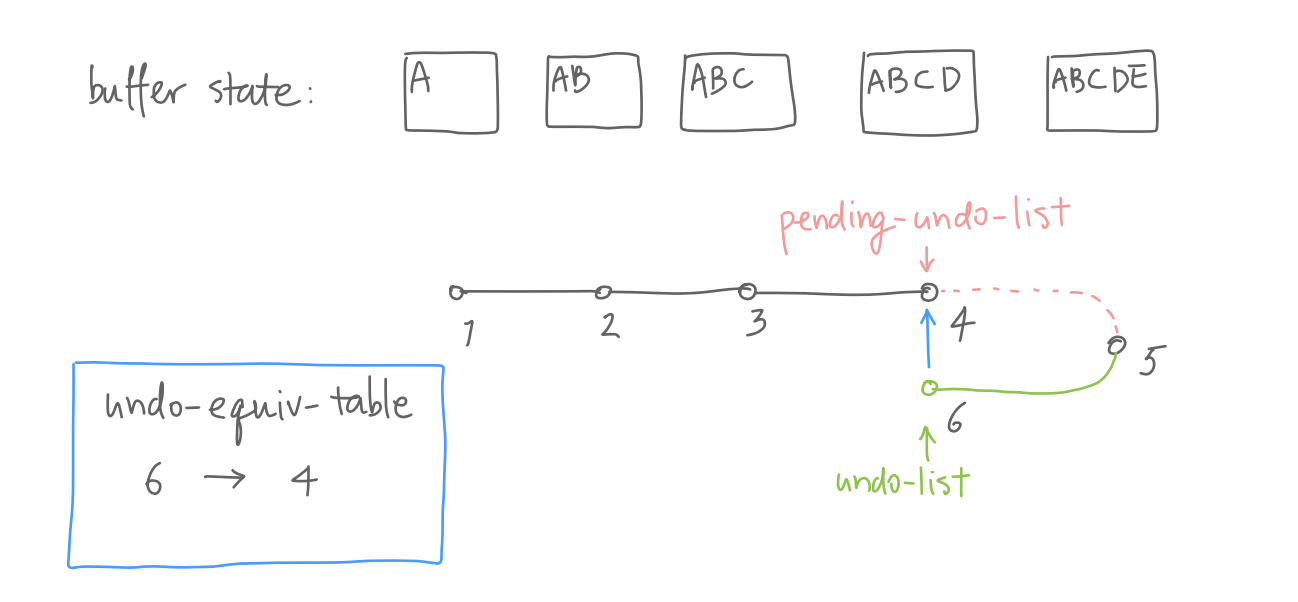

How does this “undo chain” work? When we invoke the first

undo command, it sets pending-undo-list to the

value of buffer-undo-list; further undo commands

pop modifications from pending-undo-list and

extend buffer-undo-list. And when we break the

undo chain, the next undo command will once again set

pending-undo-list to the value of

buffer-undo-list.

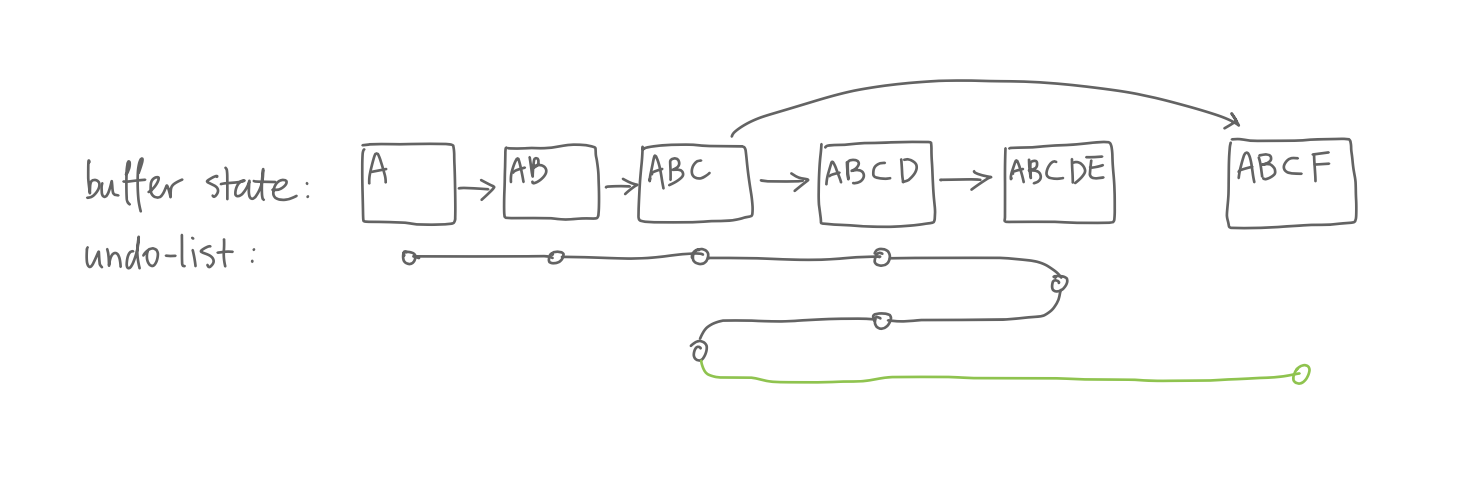

Here’s what happens when branching occurs: if we undo to

“ABC”, and insert “F”. Emacs simply pushes a new modification

to buffer-undo-list, just like before.

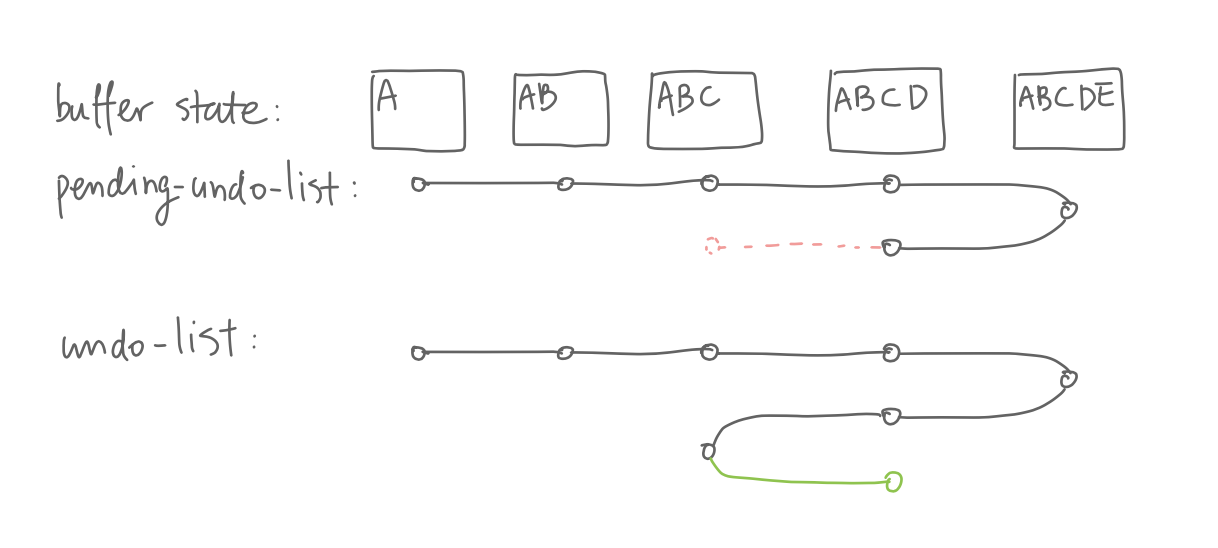

Besides extending buffer-undo-list, Emacs

also maps buffer states to their equivalents. After Emacs

undid a modification, it maps the tip of

buffer-undo-list to the tip of

pending-undo-list in

undo-equiv-table. This is the key to construct a

tree from the linear undo list.

BTW, as shown in the figure,

pending-undo-list and

buffer-undo-list are really pointing to the same

list object, just different cons cells in that list.

2 Constructing the tree

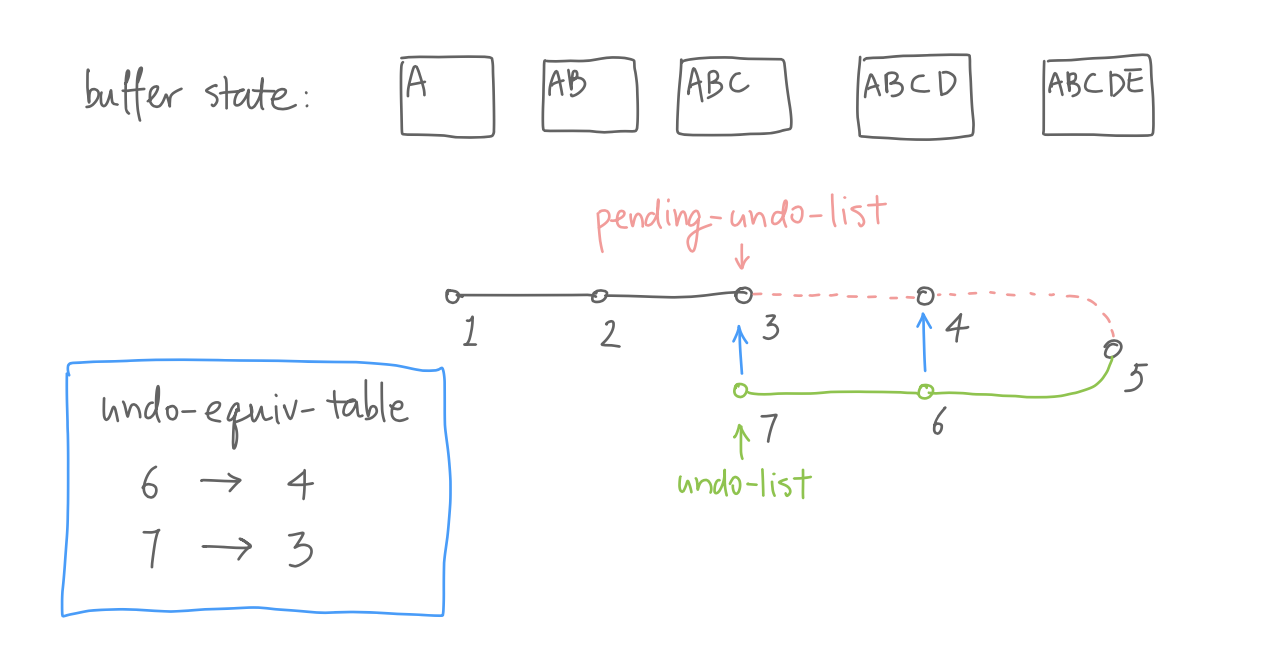

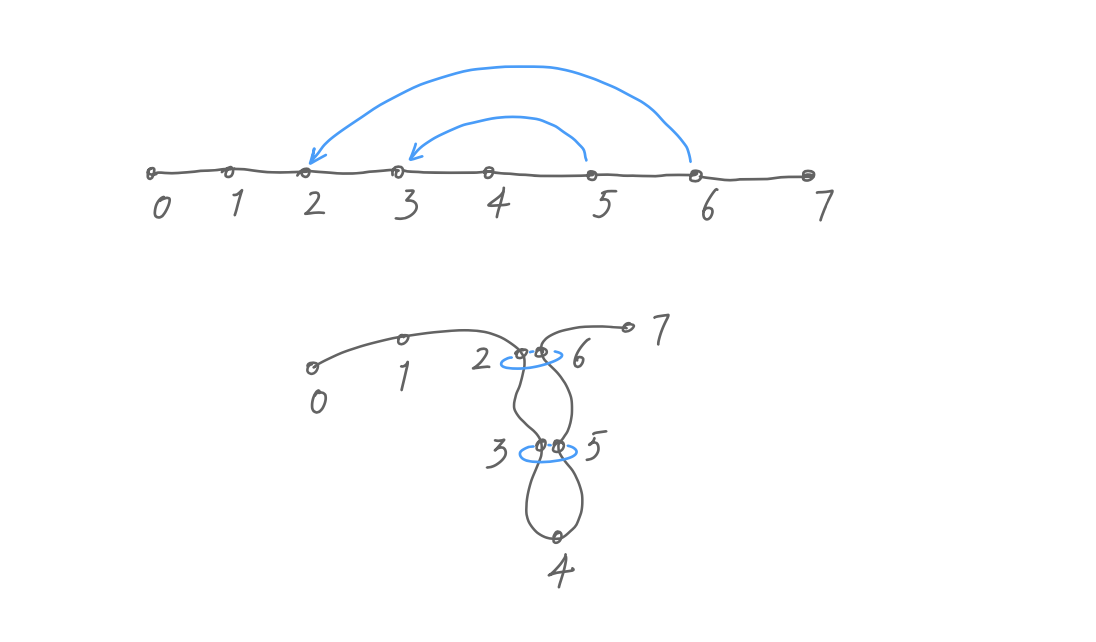

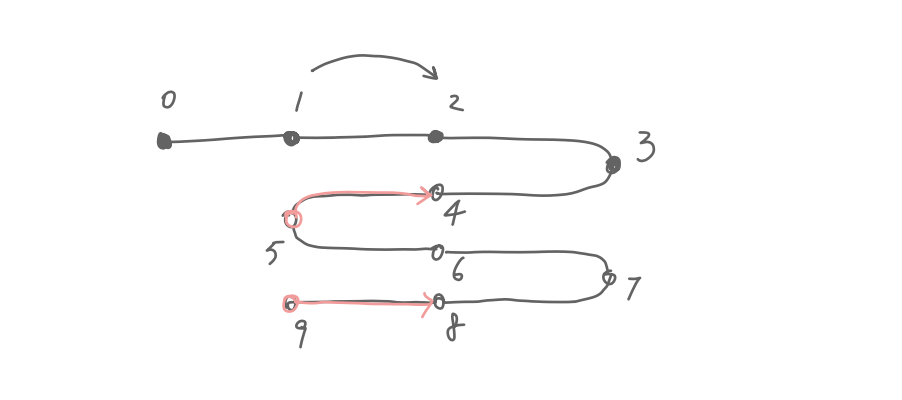

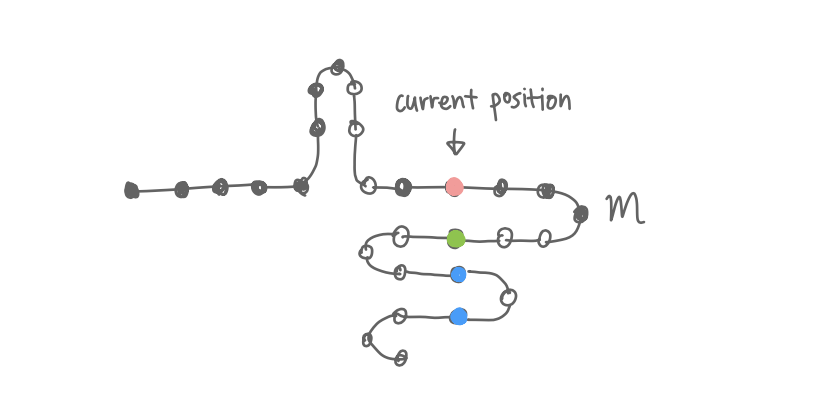

Here is an example undo tree and the corresponding undo list. The undo list can be viewed as “wrapping around” the tree. To “construct” the tree out of the undo list, we need to know:

- Which node to show. In the list, node 5 and 6 are duplicates of earlier nodes and don’t need to appear in the tree.

- Establish parent-child relationships between nodes. Starting with node 0, it needs to know node 1 is its child, node 1 needs to know 2 is its child, and so on.

Both are easy to figure out with the help of

undo-equvi-table: For a modification m

(the modification that creates buffer state m), if it

is an ordinary change, buffer state m must be a child

of m-1; if m is an undo change, then buffer

state m must be equivalent to a previous node, say,

n. m equivalent to n means 1) we don’t

draw m in the tree, only n, and 2) children of

m are children of n.

In this example, 2 is an ordinary modification, so 2 is a child of 1. 6 is an undo modification and is equivalent to 2, so we don’t draw 6, only 2; and 6’s child, 7, becomes 2’s child.

So it turns out that constructing the tree is simple: we

first go over buffer-undo-list to generate a

list of modifications. Then we go over the modification list,

identify equivalent nodes and establish parent-child

relationships. In the end, we can draw out the tree starting

from the first node, either depth-first or breadth-first.

3 Moving around the tree

Drawing out the tree is only half the story, the undo tree isn’t of any use if we can’t go back and forth in time by moving around on the tree. Say we are at node m and want to move to node n. What should Emacs do to bring us back?

My immediate thought is to just repeatedly call

undo until we are at node n. It works,

but only within 10 yards: simple movements could easily

explode the undo list. For example, suppose we are at node 1

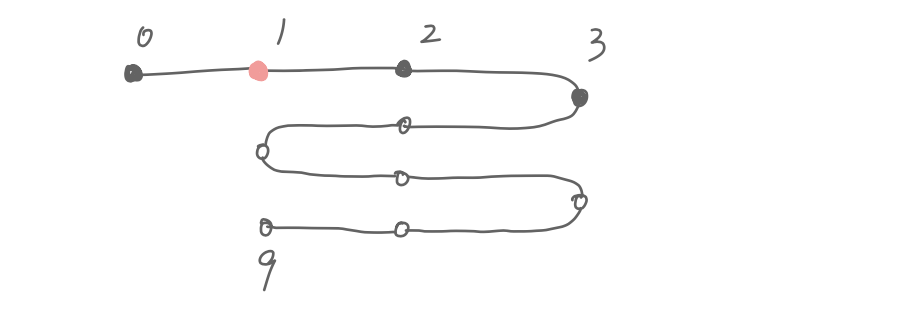

and move back to node 0, what happens to the undo list?

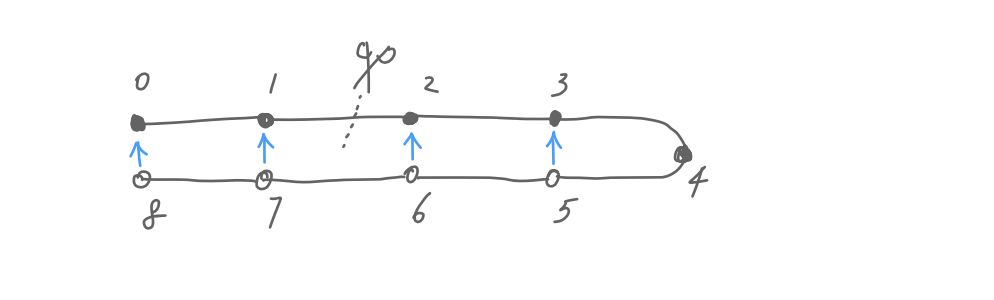

We need to undo from 9 all the way back to 0, going back and forth between 1 and 3. Worse, if we now want to go from 0 to 1, we need to undo from 18 to 1. The undo list doubles every time we move back and forth between 0 and 1.

Hmm, if we are in an undo chain, undoing from 1 to 0 would

be so much easier: pending-undo-list would point

at 1 (instead of 9), and we simply undo modification 1. Why

don’t we just do that, regardless of whether we are in an

undo chain? During chained undo, undo pops

modifications from pending-undo-list and feeds

them into primitive-undo. We can similarly find

the modification between 0 and 1 and just feed it to

primitive-undo.

Let’s look at it more closely. If I want to go from buffer

state 1 to 2, how do I find a list of modifications to feed

to primitive-undo? We can feed it modification 5

to go 5–4, or modification 9 to go 9–8, both of them move us

back to the buffer state at node 2. Or we can even go

9–8–7–6–5–4, or 5–4–3–2.

So, to find a valid “route” from m to n, it

needs to satisfy: 1) the start is equivalent to m and

the destination is equivalent to n, and 2) the start

is older than the destination, i.e., start >

end, because primitive-undo can only take

us backwards in the undo list. Once we found all the valid

routes, we pick the shortest one and feed it to

primitive-undo, teleport!

3.1 A small problem

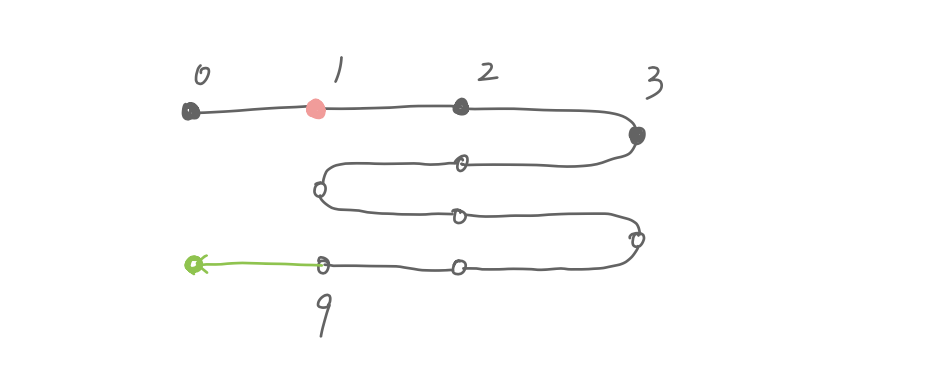

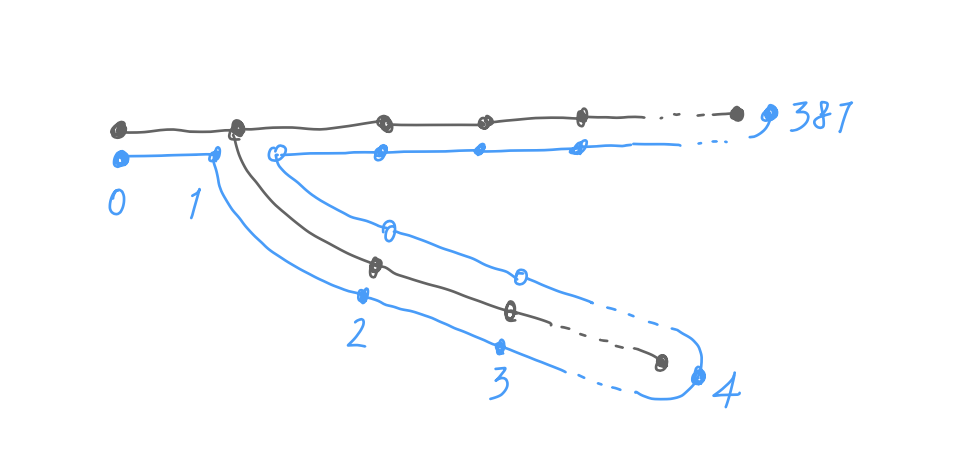

Even though we can move between nodes with minimum steps, it is still possible to extend the undo list indefinitely by simply moving around. For example, jiggling between nodes 0 and 1 in this tree keeps growing the undo list.

The previous example looks innocuous because there is

only one modification between 0 and 1. It is another story,

however, to move between two distant nodes. Consider this

example: moving between the tip of the two branches, node 4

and node 387, appends hundreds of modifications to the undo

list. If we move back and forth between them,

buffer-undo-list quickly grows to thousands of

modifications and slows down the processing of it. Worse,

because the capacity of buffer-undo-list is

limited, we might lose old records.

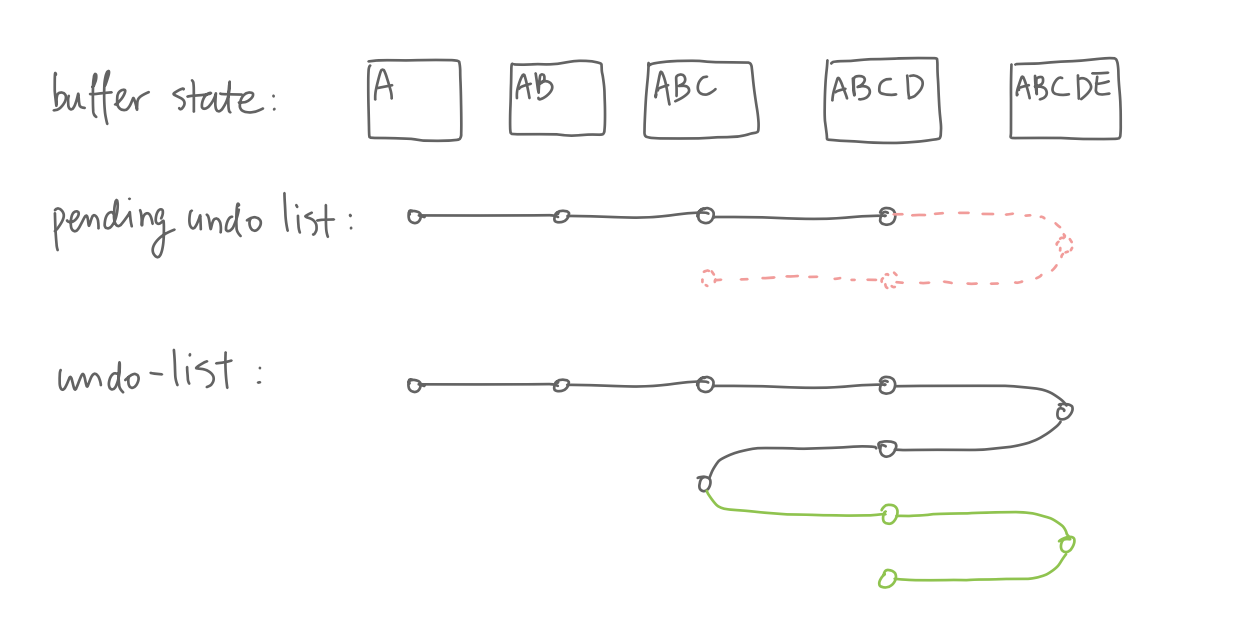

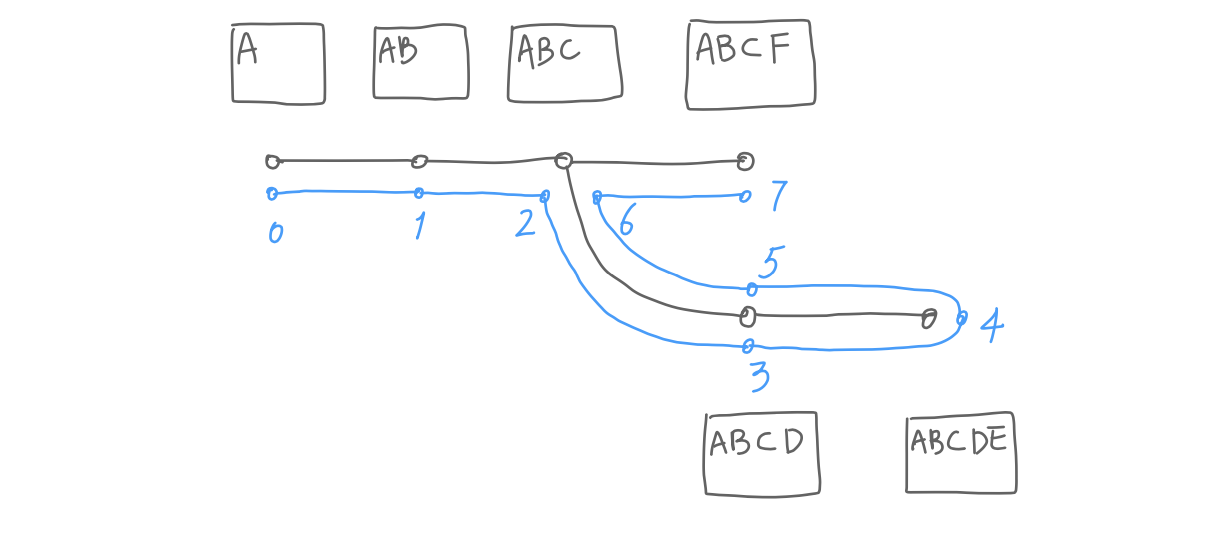

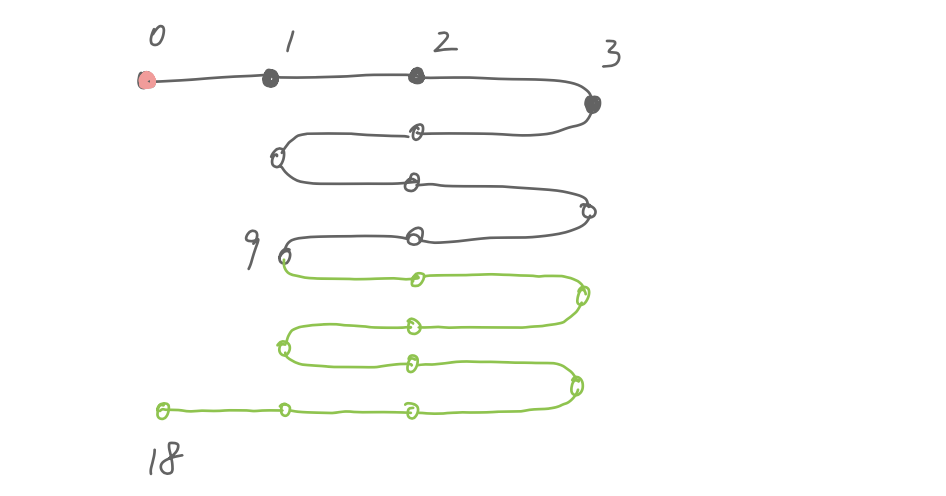

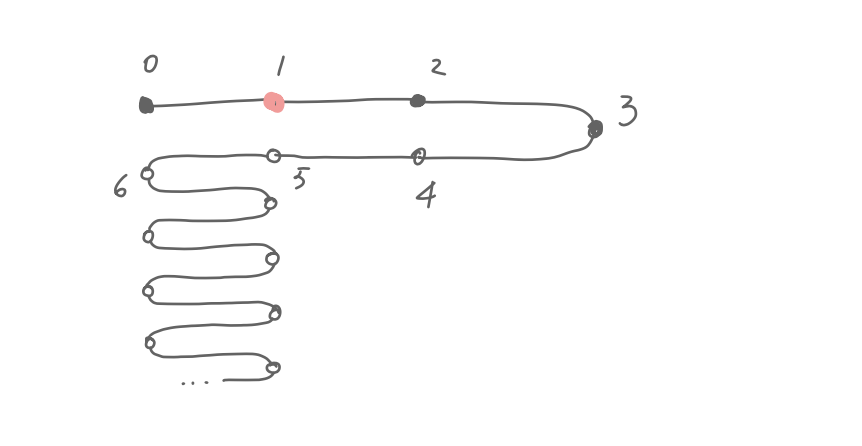

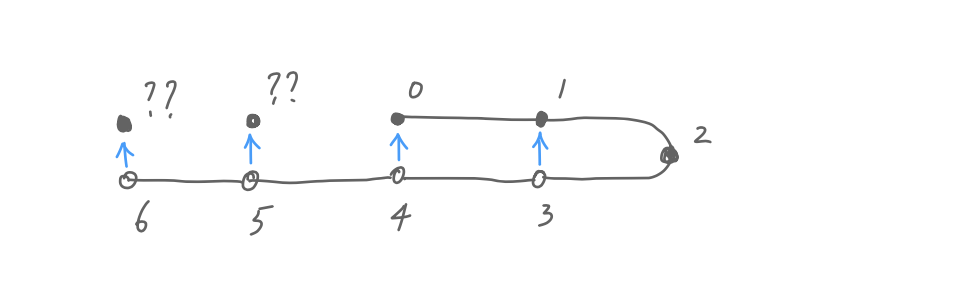

Let’s come back to this tree. Don’t all those modifications on the bottom look excessive? We don’t lose any information if we trim them off. The question is, how to identify nodes that can be trimmed off without damaging the undo tree?

We have mentioned that there are two types of modifications: ordinary modifications created by the user doing some edit, and undo modifications by undoing a previous modification. Among these two types, only ordinary modifications create new buffer states. Undo modifications, on the other hand, only bring us back to previous states. That means the complete undo tree is preserved as long as our undo list preserves all the ordinary modifications.

Consider this tree where black circles represent ordinary modifications and white circles represent undo modifications. The node m is the last ordinary modification in the undo list. We only need to preserve the undo list from the beginning to m to preserve the undo tree, plus the undo list from m to the green node to bring us to the current position. Any modifications beyond the green node is dispensable. In other words, we keep all the ordinary modifications in the undo list and trim after that at the earliest node corresponding to the current position.

Now we can move around the tree efficiently, and the

length of buffer-undo-list is bound. My

crystal ball tells me there is only one problem left.

3.2 Another small problem

As a bonus service for its loyal customers, the garbage

collector trims buffer-undo-list

automatically.

I’m flattered, does that mean some cons cells will

quietly disappear when the lisp machine decides to collect

some garbage in the middle of my code? Luckily, that’s not

the case. The garbage collector doesn’t release cells in

buffer-undo-list when there are references to

them besides buffer-undo-list 3. Since the

data structure we generated refers to cons cells in the

undo list, the boys are safe as long as we hold on to our

data structures.

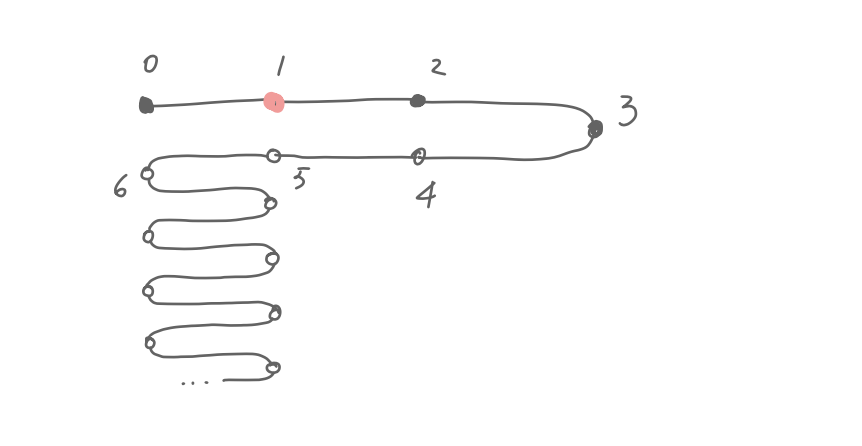

Of course, we can’t let the undo tree grow forever. And when we let the garbage collector trim the undo list, it inevitably damages our precious little tree.

Consider this undo tree, if the garbage collector releases the first two modifications, then they don’t end up in our modification list. In this case, we don’t regard the last two modifications as undos anymore, they are now normal edits. This is a bit weird as we now have two branches, but that’s just the fact of life.

4 Show me the code

;; Simplified definition of `vundo-m'. (cl-defstruct vundo-m ;; As a modification in the mod list: idx undo-list ;; A doubly-linked list of equivalent states: prev-eqv next-eqv ;; As a node in the tree: children parent point)

Github, and local backup. The package requires the current development branch of Emacs, i.e., Emacs 28. The flow of the program is roughly:

- Kick-start the process in

vundo--refresh-buffer. It determines if we are generating everything from scratch, or incrementally updating our data. - Generate a list of modifications from

buffer-undo-listbyvundo--mod-list-from. - Build the tree by

vundo--build-tree - Draw the tree by

vundo--draw-tree. - Move around by

vundo--move-to-node. It also trimsbuffer-undo-list.

Each modification is stored in a vundo-m

struct, it also represents the corresponding buffer state and

the corresponding node in the tree.

Footnotes:

Normally when you insert “ABCDE”, the individual changes are amalgamated into one. Here, for demonstration’s sake, we assume each insertion creates a separate record.

Any command other than undo

breaks the undo chain.

Although the cons cells are not released,

buffer-undo-list does shrink. That’s fine

because all the information we need are stored in our data

structures, which don’t change.